Color Theory Helps Explain Our Relationship to Nature and Wellbeing

Unless you’ve been off the grid during the past several years, chances are good you’ve heard of “millennial pink.” It seemed to be all the rage from fashion to textiles to Instagram-worthy photos taken with rose-gold iPhones. While this shade of pink made the rounds as color of the year, there’s perhaps a lesser known variety of the hue that has more profound implications than just popularity.

Baker-Miller Pink, better known as “drunk tank pink,” is a bubble-gum colored variation of pink that has been used in some prison cells to calm irate inmates1. That’s right—there is such a thing as pink prison cells. According to the book, “The Power of Color,” Dr. Alexander Schauss is credited with linking the calming effect of pink on inmates who displayed angry or antagonistic behavior2. When locked in a cell painted a saturated pink hue (think Pepto Bismol) for just 15 minutes, prisoners were noticeably calmer.

Before you don a pair of rose-colored glasses or paint every wall in your next corrections project pink, there is a flip side to this scenario. First, subsequent studies found conflicting results, and the effects are short-lived. Even worse, once a person acclimates to the surroundings, he or she may become even more irritated or violent than before3.

What’s the point? This anecdote suggests that color is a powerful tool that can have a significant impact on people and influence behavior, for better or worse. As such, this article will examine in greater detail the nature of color and the history of color choices; it will uncover both some of the psychological and physiological benefits of color as well as the drawbacks; it will help illustrate the relationships between nature, color, biophilic design and wellness; and it will identify how color can improve important concepts like safety and wayfinding.

The Science of Color

Before we dive into the power of color to influence behavior and wellbeing, let’s take a look at what color is, scientifically speaking, and how humans perceive it.

For most of history, visible light was the only known part of the electromagnetic spectrum, which represents the complete range of electromagnetic radiation from gamma rays to radio waves. The ancient Greeks recognized that light traveled in straight lines and studied some of its properties, including reflection and refraction4.

The visible light spectrum includes the range of frequencies that are visible to the human eye. Cone shaped cells in our eyes act as receivers tuned into the range of wavelengths between 380 to 400 nanometers to roughly 700 nanometers. Frequency refers to the amount of wavelength cycles that pass by in one second. Shorter wavelengths have higher frequencies, and generally, radiation (with short wavelengths) has more energy and is more harmful to humans5. Statistically, people prefer the shorter wavelengths in the visible light spectrum (such as the color blue) to the longer ones.

Colors can be identified and classified by three basic characteristics:

- Hue is the name of a color.

- Value/Tone is the amount of lightness or darkness (how much white or black is incorporated) of the hue. Low values are darker and referred to as shades, while high values are brighter and referred to as tints.

- Chroma/Saturation is the vividness (pale to intense) of color. Low chroma looks washed out while high chroma is more vivid. In other words, this describes saturation as it moves either toward or away from grayscale values.

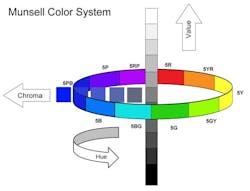

The way we visually match color today is due in large part to Albert H. Munsell’s work, who published the “Munsell Manual of Color” in 1929. It was intended to reach a wide audience to help facilitate a basic understanding of the color system and to spark an interest in and appreciation of color6.

The Munsell Color Theory is based on a three-dimensional model in which each color is comprised of the three attributes listed above: hue, value and chroma. The Munsell color system is set up as a numerical scale with visually uniform steps for each of the three-color attributes. Each color has a logical and visual relationship to all other colors, but it is much easier to understand in a three-dimensional model.

Hue, or the color itself, is indicated by a number and letter; for example, 5R for red. Hue may run anywhere between 1 to 10 in increments of 0.25. Value, or how light or dark the color is, is indicated by a number. A value of 2, for instance, indicates a color darker in value (versus a higher number which would be lighter) that may run anywhere from 1 to 10.

Chroma, or how weak or strong a color is, may be expressed as a number between 2 and 16 in increments of two. If a color has a value of 2, it indicates a weak color (versus a higher number which would be stronger). These three attributes make up the color notation, which is also referred to as its color name (5R 2/2, for example).

This article is advertiser sponsored

Industrial complexes use yellow- and black-painted lines on floors and on security railings to indicate where it’s safe to walk within high traffic areas.

In the early half of the 20th century, the Association’s primary purpose was to support textile manufacturers in creating market-ready products for the ready-to-wear industry. Back then, the organization’s committees included hat, glove and hosiery manufacturers—the trendsetters of the day. Today, that scope has broadened to include carefully selected thought leaders in the areas of fashion, accessories, product and interior design to work with CAUS on Interior/Environmental forecasts.

Members come from more than 73 industries including branding and advertising, automotive, beauty, health, cosmetics, apparel, communications, electronics and flooring. This vibrant and ever-growing professional set ranges from architects to fashion, graphic, product, industrial and interior designers facing the increasing complexity of making color decisions.

Likewise, the Color Marketing Group (CMG) is a forum for the exchange of all things color. As a not-for-profit international association of color design professionals, CMG’s members represent a broad spectrum of designers, marketers, color scientists, consultants, educators and artists. Since 1961, it has been turning a shared passion for color into business opportunities across industries. Members come together at local and international events to interpret, create, forecast and select colors with the goal of enhancing manufactured goods. By continuously collaborating, CMG better identifies the direction of color and design trends and then interprets that information across industries21.

As these organizations are well aware, the influences of color are everywhere—the environment, social issues, changing political climates, fashion, interiors—and they all impact color in one industry which has a reverberating effect on another. The only way to stay competitive in such an ever-changing environment is by harnessing each other’s endless flow of knowledge and understanding.

The Role of Color in Biophilia

A great example of color’s influence on the human psyche is one of the fundamental design attributes of the biophilic design movement. Biophilic design dates back to the early 1980s when the biologist Edward O. Wilson outlined his philosophy of “biophilia,” hypothesizing that humans have an innate, biological affinity for the natural world22. In other words, Wilson suggested we are linked instinctively to nature throughout the span of human history physically, cognitively and emotionally.

Dense constructed and engineered environments, on the other hand, which are dominated by hard surface, high-rise buildings and technology have only been prevalent for less than 0.2% of the human timeline. Thus, from an evolutionary standpoint, separation from the natural world is unnatural.

The factors that enabled our ability to survive and thrive within nature during the 99.8% of our evolutionary history are numerous, including an intimate understanding of place, seeking shelter for protection, an ability to find food and a propensity for exploration. These traits are locked into our genetic memory and explain the complex connections between humans and natural systems.

Biophilic design takes these concepts a step further by applying them to today’s “natural habitat,” the built environment where we now spend 90% of our time. This involves nature as the focal point of a building and often includes color palettes that calm, soothe and offer peaceful settings in which occupants conduct the stressful activities of work and life.

Our visual connection with nature has evolved from research on visual preference and responses to views of nature showing reduced stress, more positive emotional functioning and improved concentration and recovery rates23. Stress recovery from visual connections with nature has reportedly been associated with lowered blood pressure and heart rate; reduced attentional fatigue, sadness, anger and aggression; and improved mental engagement/attentiveness, attitude and overall happiness. There is also evidence for stress reduction related to both experiencing real nature and seeing images of nature.

Research indicates that people’s preferred view of nature is looking down a slope to a scene that includes copses of shade trees, flowering plants, calm non-threatening animals, indications of human habitation and bodies of clean water24. This is often difficult to achieve in the built environment, particularly in already dense urban settings. Nevertheless, the psychological benefits of nature increase with higher levels of biodiversity and not with an increase in natural vegetative area25.

Likewise, studies show that mood and self-esteem are positively impacted within the first five minutes of experiencing nature, such as through exercise within a green space26. Further, viewing nature for 10 minutes prior to experiencing a mental stressor has shown to stimulate heart rate variability and parasympathetic activity (i.e., regulation of internal organs and glands that support digestion and other activities that occur when the body is at rest). Further, viewing a forest scene for 20 minutes after a mental stressor has shown to return cerebral blood flow and brain activity to a relaxed state.

Dimensions of Biophilia

When most people think of biophilia or biophilic design, they most likely associate it with a term called Organic Naturalistic Dimension, which refers to shapes and forms that directly, indirectly or symbolically reflect nature. This may include direct contact with self-sustaining features (sunlight, plants, animals, ecosystems); indirect contact or a connection that requires human intervention (potted plants, fountains, aquariums, etc.); or symbolic, in which there is no actual contact with nature, but a vicarious connection is made through mediums such as murals, pictures or videos. Viewing scenes of nature stimulates a larger portion of the visual cortex than non-nature scenes, which triggers more pleasure receptors in the brain leading to prolonged interest and faster stress recovery29.

For example, heart rate recovery from low-level stress, such as from working in an office environment, has shown to occur 1.6 times faster when the space has a glass window with a nature view, rather than a high-quality simulation (i.e. plasma video) of the same nature view or no view at all.

Place-based or Vernacular Dimensions, on the other hand, offer a connection to the culture or ecology of a specific geographic area. For example, at one time, architecture was necessarily based on place. By looking at a structure, one could tell what materials were found in the region, what the weather was like and what was important to the people that lived there (think igloos, the Parthenon, etc.). In other words, architecture gave insight into the essence of a particular place.

This distinctiveness created a special relationship between people and the places they inhabited—a connection that is largely absent in our buildings today, which are increasingly homogenous across the planet. Therefore, creating place-based relationships is essential to biophilic design because doing so inherently promotes the human need for a sense of familiarity, connectedness and emotional attachment.

A good illustration of place-based or vernacular dimensions can be seen in the Google Chicago headquarters, which features unique art installations that celebrate Chicago’s history on every floor, from its transit system to famous parks. The office incorporates historical references through art installations and an industrial structure that fosters a distinct sense of place.

6 Elements of Biophilia

When it comes to incorporating natural elements within interiors to elicit a connection to nature, there are a number of different strategies and features that can be used to employ biophilia successfully. Stephen R. Kellert, professor of social ecology at Yale University, has categorized the types and functions—or Elements and Attributes as he labels them—of biophilic design30.

Specifically, there are six design elements involved in biophilic design which also include 70 subsequent design attributes across the following categories:

- Environmental Features

- Natural Shapes and Forms

- Natural Patterns and Processes

- Light and Space

- Place-Based Relationships

- Evolved Human-Nature Relationships

The first and perhaps most prominent design element listed above is Environmental Features, which involves the use of relatively well-recognized characteristics of the natural world in the built environment. Within this first category, Kellert identified 12 specific attributes associated with it that are used in the design of the built environment to reinforce ties to nature, including:

Environmental Features/Attributes

- Color

- Water

- Air

- Sunlight

- Plants

- Animals

- Natural materials

- Views and vistas

- Façade greening

- Geology and landscape

- Habitats and ecosystems

- Fire

It is no accident that in the hierarchy of biophilic design, the first design attribute of the first element is color. As Kellert explains, “The first and most obvious of the biophilic elements is environmental features. [These are] well recognized-characteristics of the natural world in the built environment.”

Interestingly, a majority of these attributes have very robust nature-color ties. Additionally, a number have strong connections to hues with shorter wave lengths on the visible spectrum in the blue-green range. Why is color so important in supporting biophilic design principles? Because color has long been instrumental in human evolution and survival, enhancing the ability to locate food, resources and water; to identify danger; to facilitate visual access; to foster mobility; and more.

Also, people want to see and are attracted to bright, flowering colors, rainbows, beautiful sunsets, glistening water, blue skies and other colorful features of the natural world. As such, incorporating a number of these attributes helps establish those connections with human instinct and the natural environment.

It’s also no coincidence that the second biophilic design attribute among the 70 that Kellert has identified is water. “Water is among the most basic human needs and commonly elicits a strong response in people … the effective use of water is design is contingent on perceptions of quality, quantity, movement, clarity,” according to Wallace Nichols, author of the book, “Blue Mind”31.

In fact, humans’ innate connection to water is so strong, there is a whole field of neuroscience developing around the concept of the “blue mind.” This theory refers to how exposure to bodies of water can heal mental injuries and improve cognition and mood.

Nichols tells USA Today: “Aquatic therapists are increasingly looking to the water to help treat and manage PTSD, addiction, anxiety disorders, autism and more. We’ve found that being near water boosts creativity, can enhance the quality of conversations and provides a backdrop to important parts of living—like play, romance and grieving32.”

Simply put, water can bring out strong positive feelings in building occupants when thoughtfully incorporated into the design. But using water as a design feature involves a delicate balance between form and function, as keeping mildew and mold from forming is an imperative that needs constant attention.

Beyond color and water, many of the remaining Environmental Attributes in Kellert’s list include plant and botanical themes. The reason is simple: humans’ tie to plant life is so strong that the shape of plants also evokes feelings of nature, which can have a positive impact on their wellbeing.

As such, the second of the six biophilic Design Elements after Environmental Features is Natural Shapes and Forms, which includes the following attributes:

- Botanical motifs

- Trees and columnar supports

- Animal (mainly vertebrae) motifs

- Shells and spirals

- Egg, oval and tubular forms

- Arches, vaults and domes

- Shapes resisting straight lines and right angles

- Simulation of natural features

- Biomorphy

- Geomorphology

- Biomimicry

The first two elements on this list have strong connections to plants, trees and other fauna. This is notable because Kellert posits that the shapes and forms of plants are important design elements. These shapes can mimic or simulate plant forms such as foliage, ferns, cones, bushes, etc. Likewise, the appearance or simulation of tree-like shapes, especially columnar supports, is a common and desired design feature. These columns can include leaf capitals which can evoke a forest setting in a room when multiple shapes are used.

These connections between the natural and built environments describe another term called biomimicry. Coined by Janine Benyus in 1997, biomimicry is the practice of borrowing adaptations functionally found in nature and applying them to architectural designs. Examples are structural and tensile properties, adhesion, air conditioning, photosynthesis, etc., that are found in natural species now used in building materials and shapes.

Informing Signage and Wayfinding

What do signage and wayfinding have to do with the discussion color and biophilia? One need look no further than human history and the natural world to make the connection to signage.

Imagine you are back in a pre-industrial time, in a forest, collecting mushrooms or traveling with your family to a summer gathering. How do you know (and how did your ancestors know) which path to take or which forest or bog to avoid when traveling through the natural world? To indicate the correct path, a mark would be scored into a large tree trunk or a dye mark placed on a large stone at a fork in the road. To show distances, rocks were often stacked. Each of these methods provides information to travelers through signs and size. They are made through convention and read without spoken or written words.

Shape is also important in signage. To symbolize a sacred spot for council meetings, the Odawa Indians of Northern Michigan would pull and shape the trunks of 12 to 20 trees into a circle to create a bower. Of these council circles, many remain with one or two trees still standing after 150 to 200 years where the space was protected by the landowner from logging operations.

The role of shapes can also be seen in pre-industrial signage as well. Early introductions to modern signage can be traced back to the Greeks and Romans, who made signs using stone or terra cotta emblazoned with imagery more than text due to a high rate of illiteracy33. These signs contained specific symbols to identify business that used raw materials like wood, leather, stone or metals. Likewise, early Christians used the shape of the cross to indicate places to meet, while other religions used symbols like the sun and moon34.

So, how is signage used in the modern built world? Frequently, color is used to give meaning. For instance, while traveling down the street to go shopping or to gather with friends, traffic lights and stop signs appear at regular intervals. Traffic lights have green, yellow and red lights, and are painted bright yellow. Stop signs and yield signs are red and white. Street signs are typically green with white letters, or white with black letters, depending on the region. These bold colors communicate when it is safe to proceed or when we need to stop or exercise caution to avoid injury or even death.

Inside hospitals and manufacturing complexes, color can be used without words to guide visitors and employees. Many hospitals now use color stripes on the floor, walls or wall base, each representing a different department (e.g., oncology, pediatrics, payments, etc.) for guests to follow to their destination. Oftentimes, purples, blues and greens are used for these striped guides.

Many hospitals now use color stripes on the floor, walls or wall base, each representing a different department (e.g., oncology, pediatrics, payments, etc.) for guests to follow to their destination.

Likewise, industrial complexes use yellow- and black-painted lines on floors and on security railings to indicate where it’s safe to walk within high traffic areas where forklifts may be operating, near moving manufacturing equipment or material or product storage.

Color and signage can also be used to demonstrate affiliation today as it was in ages past. In medieval Europe, for instance, important houses and regions used family crests on shields and clothing to establish connection and loyalty. How do we show our modern tribal affiliations? With mascots and logos and crests on everything from clothing to bedding and walls to floors in dual or full color. While things have certainly changed over time, some things stay the same.

Certifiably Healthy (and Beautiful)

Health and wellness is perhaps the leading trend in the design industry at the moment—not only in the workplace, but across multiple markets including education, healthcare and hospitality. The industry is at a tipping point as it relates to this trend, with an increasing number of companies showing interest in and taking steps toward providing healthier spaces for building occupants.

As such, the industry has seen tremendous growth in projects that are registered with or have achieved The International WELL Building Institute’s (IWBI) WELL certification, the Center for Active Design’s (ACD) Fitwell certification and the International Living Future Institute’s (ILFI) Living Building Challenge.

Among these programs, the Living Building Challenge is one of the built environment’s most ambitious holistic performance standards. Launched in 2006 and administered by ILFI, the Living Building Challenge is organized into seven performance areas called Petals—Place, Water, Energy, Health & Happiness, Materials, Equity and Beauty35. The metaphor of a flower is appropriate in that a building can be designed to function as efficiently as a flower, according to ILFI.

Unlike biophilic design, color does not receive its own designation of achievement within the Living Building Challenge’s seven Petals; however, it certainly factors in to the “Beauty” petal figuratively and into the “Health & Happiness” petal literally through the biophilic design imperative that requires projects to be transformed by deliberately incorporating nature through Environmental Features (remember, the first attribute is color), Light and Space, and Natural Shapes and Forms.

Beauty is not something that can be mandated, but rather is judged within the Living Building Challenge based on “genuine efforts, thoughtfully applied,” according to ILFI. “The intent of the Beauty Petal is to recognize the need for beauty as a precursor to caring enough to preserve, conserve, and serve the greater good.” There are no current limitations to this Petal other than the imaginations and what we choose to value as a society.

Another sustainable building initiative focused more of the impacts of the built environment on human health is the WELL Building Standard. Many of the LBC imperatives contribute to achieving WELL certification requirements, so it is no surprise that “Beauty and Mindful Design” is one of WELL’s initiatives (Feature 87).

Although somewhat vague in nature, this design imperative states that: “A physical space in which design principles align with an organization’s core cultural values can positively impact employees’ mood and morale. Integrating aesthetically pleasing elements into a space can help building occupants derive a measure of comfort or joy from their surroundings. The incorporation of design elements and artwork to a space can create a calming environment able to improve occupant mood36.”

There is an additional component of color quality addressed by WELL that is worth noting. Although it is more specifically aimed at the quality of lighting, it still establishes the importance of the role color plays within interiors and the impact it has on occupants. “Color quality impacts visual appeal and can either contribute to or detract from occupant comfort. Poor color quality can reduce visual acuity and the accurate rendering of illuminated objects37.”

The WELL rating system’s criteria requires that to accurately portray colors in a space and enhance occupant comfort, all electric lights (except decorative fixtures, emergency lights and other special-purpose lighting) must meet the following conditions: 1. Color Rendering Index Ra (CRI, average of R1 through R8) of 80 or higher; and 2. Color Rendering Index R9 of 50 or higher. [CRI is a common way to measure color quality, capturing R1-R8 metrics. R9, while not always reported, is also included as part of this feature, as R9 values further take into consideration how we perceive the saturation of warmer hues.]

Conclusion

As this article has established, the role of color in the natural and built environments cannot be overstated. Although it can be difficult to precisely measure or predict color’s impact on people, it’s clear that its relationship to human beings is profound. It can serve some of our most basic instincts for survival as well as appeal to our higher affections for beauty.

In the built environment, we are only beginning to understand the effect that design imperatives like biophilia and color have on psychological and physiological health. But as the body of knowledge and evidence-based research continues to grow, the connections between color, nature, biophilic design and wellness are becoming clearer.

As such, designers and specifiers can make the case that color choices do matter a great deal and go beyond personal preference. A more complete understanding of color and its relationship to people and nature can help support wellbeing, inform our interactions and perceptions, and create more beautiful places to live, work and play.

REFERENCES

1, 3 Drunk Tank Pink: Does pink make strong men weak? Can pink jail cells calm violent prisoners? Retrieved from https://www.colormatters.com/color-and-the-body/drunk-tank-pink

2 Walker, M. The power of color. Avery Publishing Group. 1991. pp. 50-52. Retrieved from https://www.amazon.com/Power-Color-Morton-Walker-D-P-M/dp/0895294303

4 Electromagnetic spectrum. Wikipedia entry. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electromagnetic_spectrum

5 Tour of the electromagnetic spectrum: visible light. NASA. n.d. Retrieved from https://science.nasa.gov/ems/09_visiblelight

6 Munsell manual of color—defining and explaining the fundamental characteristics of color. Munsell Color. n.d. Retried from https://munsell.com/color-blog/manual-color-defining-fundamental-characteristics-color/

7 Grossman, R. P. & Wisenblit, J. Z. What we know about consumers’ color choices. Journal of Marketing Practice: Applied Marketing Science. 1999. 5(3), p 2.

8 Hurlburt, A. & Ling, Y. Biological components of sex differences in color preference. Current Biology. Vol. 17, Iss. 16. August 21, 2007, pp. R623-R625. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S096098220701559X

9 Regan, B, et. al. Fruits, foliage and the evolution of primate colour vision. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 2001. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230897067_Fruits_foliage_and_the_evolution_of_primate_colour_vision

10 Alexander, G. An evolutionary perspective of sex-typed toy preferences: pink, blue, and the brain. Archives of sexual behavior. 2003. 32. 7-14. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/10891579_An_Evolutionary_Perspective_of_Sex-Typed_Toy_Preferences_Pink_Blue_and_the_Brain/citation/download

11, 12 Palmer, S. & Schloss, K. An ecological valence theory of human color preference. PNAS. May 11, 2010. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0906172107

13 Gorn, G. J. The effects of music in advertising on choice behavior: A classical conditioning approach. Journal of Marketing. 1982.

14 Labrecque, Lauren & Milne, George. Exciting red and competent blue: The importance of color in marketing. Journal of The Academy of Marketing Science. 2011. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251277565_Exciting_red_and_competent_blue_The_importance_of_color_in_marketing/citation/download

15, 16 Basic color terms: their universality and evolution. Wikipedia. n.d. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basic_Color_Terms:_Their_Universality_and_Evolution

17, 18 Kolenda, N. Color psychology. n.d. Retrieved from https://www.nickkolenda.com/color-psychology/

19 Melby Clinton, et. al. Glamour. December 8, 2014. Retrieved from https://www.glamour.com/story/how-does-pantone-pick-color-of-year

20 Color Association of the United States. n.d. Retrieved from http://www.colorassociation.com/

21 Color Marketing Group. n.d. Retrieved from https://colormarketing.org/

22 Schwab, K. What is biophilic design, and can it really make you happier and healthier? Fast Company. April 11, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/90333072/what-is-biophilic-design-and-can-it-really-make-you-happier-and-healthier

23 Browning, W., et. al. The 14 Patterns of Biophillic Design; Improving Health and Well-being in the Built Enviroment. Terrapin Bright Green. 2014. Retrieved from https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/14-patterns/

24 G.H. Orians & J.H. Heerwagen. Evolved responses to landscapes. J.H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, J. Tooby (Eds.), The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture, Oxford University Press. 1992. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1618866718301146#bib0320

25 Fuller, et. al. Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity. Biology Letters. Aug. 22, 2007. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17504734

26 Barton, J. & Pretty, J. What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environmental Science & Technology. 2010. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20337470

27 Brown, D., Barton, J. & Gladwell, V. Viewing nature scenes positively affects recovery of autonomic function following acute-mental stress. Environmental Science & Technology. June 4, 2013. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3699874/

28 Tsunetsugu, Y. & Miyazaki, Yoshifumi & Sato, H. Visual effects of interior design in actual-size living rooms on physiological responses. Building and Environment. 2005. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222763222_Visual_effects_of_interior_design_in_actual-size_living_rooms_on_physiological_responses/citation/download

About the Author

Robert Nieminen

Market Content Director

Market Content Director, Architectural Products, BUILDINGS, and interiors+sources

Robert Nieminen is the Market Content Director of three leading B2B publications serving the commercial architecture and design industries: Architectural Products, BUILDINGS, and interiors+sources. With a career rooted in editorial excellence and a passion for storytelling, Robert oversees a diverse content portfolio that spans award-winning feature articles, strategic podcast programming, and digital media initiatives aimed at empowering design professionals, facility managers, and commercial building stakeholders.

He is the host of the I Hear Design podcast and curates the Smart Buildings Technology Report, bringing thought leadership to the forefront of innovation in built environments. Robert leads editorial and creative direction for multiple industry award programs—including the Elev8 Design Awards and Product Innovation Awards—and is a recognized voice in sustainability, smart technology integration, and forward-thinking design.

Known for his sharp editorial vision and data-informed strategies, Robert focuses on audience growth, engagement, and content monetization, leveraging AI tools and SEO-driven insights to future-proof B2B publishing.