The late Steve Jobs famously observed that “Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.” His insight into the importance of both form and function is what has kept Apple at the forefront of the tech industry, and the same can be said for the world of interiors.

The firms and designers who understand that aesthetics and functionality go hand in hand and inform each other are the ones that typically succeed in creating inspiring spaces people want to inhabit. And yet, when most people consider a well-designed space, the emphasis remains on how it looks. For too long, design has focused on our sense of sight (as well as touch) and neglected how a well-designed interior sounds. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the workplace today.

The ubiquitous open office plan was initially heralded as the solution to improving collaboration and productivity, not to mention freeing generations of employees from working in cubicles. However, as time and experience have revealed, the open plan concept isn’t as healthy or effective as we once thought.

It’s not that open offices aren’t beautiful and offer employees more functional, ergonomic furniture or more appealing break rooms and lounge spaces. It’s that they’re simply too noisy. In fact, multiple studies and reports demonstrate that noise levels are the single biggest complaint among office workers today. While no one is arguing for the reestablishment of cubicle farms, the noise problem isn’t going away. Noise-cancelling headphones aren’t the solution because they undermine the ability of employees to collaborate, which open offices were designed to do.

Is unwanted noise really that big of a deal? Does it make that significant of a difference in the well-being and productivity of the occupants in a space? This CEU will answer those questions and others and will review the basic principles of effective acoustics; it will examine the wellness trend and how interiors can be designed to improve wellbeing with regards to sound; it will take a closer look at productivity and engagement and how they can be improved through the design of the workplace; and it will offer insight into how the materials specified in a space can help improve acoustics and, thereby, the wellbeing of occupants in the workplace, healthcare settings, educational institutions and beyond.

The High Price of Noisy Environments

As noted earlier, the open office is the predominant model for the design of the workplace today. By 2014, nearly 70% of all offices reportedly featured open floor plans1. And while the open office is here to stay, the noise problem seems to be as well, which comes with a heavy price tag.

According to the 2019 “What’s That Sound?” Workplace Acoustics Study from Interface, noisy offices increase levels of stress and anxiety for employees, and more than half of respondents indicated that noise levels would impact their decision to accept a job at a company2.

The report identified the most common causes of office noise that disrupt people’s work in the U.S., U.K. and Australia. For American employees, the biggest sources of unwanted noise are: co-workers talking to one another (76%), talking on the phone (67%), phones ringing (65%), people walking around (56%) and printer/fax machines in use (45%). (Note: Keyboard clicking was not identified as a source of distraction in the U.S. but 47% and 39% of those surveyed in the U.K. and Australia, respectively, considered it unwanted noise.)

All this noise is more than just annoying or irritating; it negatively impacts workflow and productivity as well. Here’s why: simply put, noise disturbs concentration, and that’s a big deal when people spend more than half of their time performing tasks that require concentration, according to architecture and design firm Gensler3.

There’s a kind of irony at play here as well, in that most workers struggle to concentrate in open plan environments that were designed purely for collaboration4. Further, while people can adapt to the steady sound of background noise (or “white noise”), what impedes productivity most often in the workplace is interruptive noise. Researchers at the University of California, Irvine discovered that employees get interrupted every 11 minutes and aren’t fully able to refocus on their tasks for another 25 minutes, resulting in more than 2.5 hours lost to interruptions each day per employee5. These distractions equate to roughly $650 billion in losses to American companies each year, according to a Business News Daily report.

It gets worse. By monitoring the brain activity of workers in open plan offices, one study concluded that employees are up to 66% less productive when exposed to just one nearby conversation6. Likewise, the Center for the Built Environment found in a post-occupancy evaluation of 15 buildings by more than 4,000 respondents that more than 60% of occupants in cubicles believe poor acoustics interfere with their ability to get their jobs done7. It seems even relatively small levels of unwanted noise can cause stress and hinder employees’ performance. Gary Evans, a professor of environmental psychology at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, noted that employees working in a noisy office are 40% less likely to solve technical or functional problems. And when compared with those working in quieter environments, they are also like to make only half as many ergonomic adjustments to their workspace than their counterparts8.

The reason noise poses such a problem for people is because it’s a constant source of stimulation that is difficult to ignore because the human ear is always in receiving mode. “The only solutions are room acoustics measures, modern telephony technology, and good spatial planning,” according to the Interior Business Association9. In the next section, we’ll review the basics of acoustics and spell out some common terms and definitions that are relevant to understanding acoustics.

A Primer on Acoustics

If noise is the enemy in the workplace and other interior environments like hospitals and schools, then it’s logical to assume that silence is the ultimate ally. Interestingly, when it comes to addressing noise issues or controlling sound in a space, total silence isn’t the end goal. A completely silent room like a recording studio can be a somewhat uncomfortable place to occupy, because sound is a part of our senses and is present in every environment we inhabit. Therefore, the complete absence of sound in a space can feel unnatural.

Sound only becomes noise when it’s not controlled. The aim isn’t to eliminate sound completely, but rather to balance and correct it. To conquer acoustic challenges, it’s important to “understand the enemy,” as it were. As such, knowledge of how sound works will play a key part in overcoming and preventing acoustical issues from happening.

Let’s start with the obvious and define what we mean by “sound.” In physics, sound is a vibration that typically propagates as an audible wave of pressure, through a transmission medium such as a gas, liquid or solid. In human physiology and psychology, sound is the reception of such waves and their perception by the brain.

Humans can only hear sound waves as distinct pitches when the frequency lies between about 20 Hz and 20 kHz. Sound waves above 20 kHz are known as ultrasound and are not perceptible by humans, and likewise sound waves below 20 Hz are known as infrasound and are also unreceptive to the human ear10.

Essentially, sound frequencies are divided into three main categories: low, medium and high, each with its own type of wave. Low frequencies mean fewer waves are occuring per second, which makes each individual wave longer, larger and more extended. Similar to waves in an ocean, they are more difficult to absorb than the small, rippled waves seen in higher frequencies.

All the sounds we hear have a certain frequency. Acoustic discomfort occurs when there is an imbalance between these frequency catagories, so the goal is to absorb the right amount from each to create balance. In today’s interiors, the main focus should be to absorb human speech frequencies which hover from 500 Hz to 1000 Hz in most cases.

Reviewing the ABCs (and D) of Acoustics

While the principles of controlling acoustics in interiors can be broken into a few basic categories, the process of successfully addressing noise can be a complicated undertaking. The science of acoustics is complex, and therefore, enlisting the help of an acoustic expert is prudent and recommended.

Likewise, effective acoustical design is not a one-size-fits-all strategy by any means. But following the ABCD principle—Absorb, Block, Cover and Diffuse—is a useful rule of thumb to follow11.

- Absorb. The principle of sound absorption is used to determine the amount of sound that needs to be “soaked up” or absorbed in order to reduce the amount of sound being reflected throughout the space. In other words, the culprit is reverberation when sound bounces off hard surfaces. The idea is to use sound-absorbing products such as acoustic panels to help minimize the amount of reverberation taking place.

Acoustical consultant Benjamin Wolf of ABD Engineering & Design notes that absorbing all sound isn’t the solution to the problem of reverberation. Rather, it’s about soaking up the optimal amount of noise. “We don’t simply add as much absorption as possible. Too much absorption can make a space sound ‘dead,’ which can be unnerving,” he says.

While acoustic panels don’t guarantee complete speech privacy (even those with high NRC ratings), they make a significant impact in rooms with many hard, reflective surfaces such as open offices.

Not every space can use wall mounted panels, however, so in those cases, acoustic panels can be utilized in the ceiling plane, which offers good coverage because it is as large as the floor plate and sound often bounces off of hard ceilings. While not every surface can feature acoustic panels, a good rule of thumb to follow is to utilize these products in two adjacent surfaces, which can be very effective at absorbing unwanted sound.

Additionally, upholstered room dividers and partitions with absorptive backing material can also be effective in spaces where wall or ceiling panels can’t be installed. Many of these products are also movable, which provides the added benefit of flexibility and additional visual privacy.

Further, a leading acoustic manufacturer has also developed acoustic textiles that utilize soft, interwoven polyester acoustic fibers that are effective in helping to achieve acoustic comfort in interior spaces. The patented technology allows interaction between the fiber and air, which helps control reverberation while adjusting the environment’s acoustics with precision. The choice of different materials and installation modes allows for selective absorption at precise ranges (low, medium, high) or a more uniform absorption at all frequencies.

- Block. The same rule that applies to absorption is applicable with blocking: not all sound should be obstructed from traveling within a space, but rather, it’s about impeding the ideal amount of the right sounds in the most effective way. The challenge with blocking sound has less to do with reverberation as with transference between rooms. Sound- blocking materials with high STC ratings can be specified in walls, carpet and workstation panels, for example, but it can be challenging in open offices were partition heights are low, according to Wolfe.

- Cover. In noisy environments such as an open office, or schools or hospitals, sound masking products and systems that create white noise can be an effective way to eliminate distractions and create speech privacy when covering is important. This is done with sound masking. In other words, if a space doesn’t contain sound-absorbing or blocking elements, the danger is adding additional noise to a room with nothing to absorb it and making the problem even worse. As such, acoustic products should be used in tandem to achieve the desired effect.

- Diffuse. In acoustics and architectural engineering, diffusion is the efficacy by which sound energy is spread evenly in a given environment. A perfectly diffusive sound space is one that has certain key acoustic properties which are the same anywhere in the space. A non-diffuse sound space, on the other hand, would have considerably different reverberation time as the listener moved around the room. In other words, noise isn’t just about the source of the noise, but it’s the reverberation. It’s the way it’s traveling back and forth and just doesn’t seem to go away. In some restaurants, for example, owners want to create a buzz and they want to have an energetic vibe, but sometimes there’s simply too much noise. So, diffusion is breaking up the sound by slightly angling a wall so it doesn’t reverberate and echo back and forth, for instance. Noise can also be diffused just through using soft art sculpture or hanging a chandelier.

According to a leading supplier of acoustic solutions, when considering the ABCs of acoustics for interiors, the most important factor to keep in mind is reverberation, measured in reverberation time (RT). Reverberation time is the period it takes for a sound that’s been emitted to no longer be audible (or the time it takes for a sound to decrease by 60 dBs from its original frequency). Sound moves in a space in many directions at once at a speed of 1,125 feet per second, so if a room isn’t properly equipped with acoustic elements to absorb it, the resulting reverberation and echo can cause noise issues.

Technically, echo is classified as an event when a sound wave reaches the ear more than 0.1 seconds after the original sound wave was heard. This explains how sensitive the human ear is to echoes. But echoes don’t need to be eliminated completely, they only need to be controlled.

Reverberation time is the most common measure of comfort when it comes to interior acoustics. There are several strategies that can be used to achieve acoustic comfort, including understanding the properties of different materials and their NRC/STC ratings, which we’ll review in detail in a later section.

The Wellness Paradigm

Given the fact the humans spend a majority of their time indoors, it’s no wonder that the industry is beginning to take a much closer look at the impact that buildings have on occupant health. Wellness is one of the most significant trends in decades and is changing the way we view the world—from the products we purchase to the buildings we inhabit.

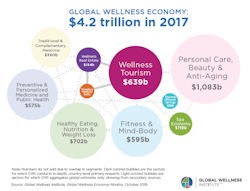

To be sure, the global wellness trend is among the largest and fastest growing industries, outpacing global economic growth by almost double (6.4% vs. 3.6% respectively between 2015 and 2017)12. The wellness market is currently estimated at $4.2 trillion annually, penetrating a wide variety of categories, including:

- Personal Care, Beauty and Anti-Aging ($1,083 billion)

- Healthy Eating, Nutrition and Weight Loss ($702 billion)

- Wellness Tourism ($639 billion)

- Fitness and Mind-Body ($595 billion)

- Preventative and Personalized Medicine and Public Health ($575 billion)

- Traditional and Complementary Medicine ($360 billion)

- Wellness Lifestyle Real Estate ($134 billion)

- Spa Economy ($119 billion)

- Thermal/Mineral Springs ($56 billion)

- Workplace Wellness ($48 billion)

The workplace wellness market, specifically, is projected to grow to $66 billion by 2022, according to the Global Wellness Institute (GWI)13. These initiatives aren’t just coming from the top down, either. Most full-time office employees (87%) who responded to a Capital One survey on their attitudes about the workplace agree that it’s important for companies to create programs and spaces that support their employees’ mental health and wellbeing14. However, 90% of workers who have access to workplace wellness programs and services are concentrated in the U.S. and Europe, the GWI noted.

On the flip side, workforce “unwellness” (chronic disease, work-related injuries and illnesses, work-related stress and employee disengagement) may cost the global economy 10% to 15% of economic output each year, the GWI estimates15.

While the numbers may seem high, consider this: employees represent an organization’s largest cost in terms of overhead, more than construction and operating costs combined16. “This statistic includes not only productivity, but also health, happiness and branding impacts. The theory goes that if these factors can be positively impacted, bottom-line savings can be significant,” according to architecture and design firm Stantec.

It’s no wonder then that the architecture and design industry has seen a steady increase in the number of projects built to achieve third-party certifications such as the International WELL Building Institute’s WELL Building Standard and the Center for Active Design’s Fitwel Certification System. To date, there are more than 650 registered Fitwel projects with over 180 projects certified or pending certification, with an 80% increase in projects achieving certification between 2017 and 201817. Likewise, there are more than 1,000 registered projects under WELL, encompassing more than 190 million square feet of real estate projects in 37 countries worldwide18. In fact, 49% of building owners today are willing to pay more for buildings demonstrated to have a positive impact on health19.

Clearly, the wellness movement is here to stay, and as such, it’s vital for designers and specifiers to understand how interiors impact occupant health. The subject is multifaceted and highly technical, so for the purposes of this CEU, we will explore further the role that acoustics plays in wellness and how the aforementioned rating systems address it.

The Role of Acoustics in Wellness

As we’ve established already, sound is a healthy, natural part of the human experience. Prolonged exposure to noise, however, is not. On the contrary, it damages human health by causing a psychological stress response in the body, including a spike in blood pressure and heart rate.

“There are well-established links between long-term exposure to noise and coronary illness and stroke, as well as stress, high blood pressure and other conditions. The noise in question does not have to be overwhelmingly loud: research shows that the danger level is just 65 dB [quieter than a home dishwasher], which is often achieved in lively offices and especially in social spaces like cafés and canteens,” according to an Interface study20.

Research has shown that even intermittent exposure to loud noises can result in negative health outcomes such as long-term stress hormone levels and hypertension21. Obviously, such stressors have a detrimental effect on employee health and productivity, which also can impact a company’s bottom line, as we’ve noted in earlier sections.

Beyond the workplace, however, the ability to mitigate unhealthy noise in settings such as educational and healthcare environments take on even greater importance.

Education Implications

Research has shown that children growing up in noisy homes develop language and cognitive skills more slowly than those who live in quieter homes. Other studies demonstrate a similar effect in classrooms, where students who are exposed to excessive noise fall behind their peers in quieter classrooms22. In one New York City school, for example, students classroom was located near a train track performed worse in reading comprehension (up to a year behind) than their peers on the other side of the school. Interestingly, when the city installed noise dampeners on the train tracks and soundproofing materials in the schools, the lagging students caught up to their peers.

Further, according to Autism Speaks, approximately 1 in 59 children is diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD), many of whom suffer from noise sensitivity. This can be particularly challenging in classroom settings, so researchers set out to determine exactly what effect noise had on students on the spectrum.

In one study, four classrooms were identified in two schools based on their noise levels, and behaviors were recorded from 42 participants. Research results indicate that environment is important to the treatment of autism because it influences behavior23. Specifically, the study uncovered a significant, positive correlation between noise levels and frequency of target behaviors among students with autism. As decibel levels increased, several of the observed behaviors occurred with greater frequency.

Overall, the study’s findings suggest that attention to acoustic design and modifications to existing environments are essential to providing a supportive educational environment24. “With decreased arousal and increased neurological resources, individuals with ASD will evidence less stereotypic behavior as a result of lower internal distress,” the study’s authors noted. “Although under some circumstances, individuals with autism may benefit from being acclimated to neuro-typical environments, providing environments that buffer acoustics benefits the learning of individuals with heightened sensory perception and individuals with neuro-typical functioning alike.”

Healthcare Considerations

There are many potentially undesirable outcomes that noise can produce in healthcare settings that range from irritating to harmful for both patients and caregivers and could affect them psychologically and physiologically. For example, a sudden noise can startle a patient and trigger reflexes that may lead to injury, increased blood pressure and/or higher respiratory rates. Patients who are exposed to noise for prolonged periods may also experience memory problems, irritation, impaired pain tolerance and perceptions of isolation. Further, being exposed to noise at all hours can lead to sleep deprivation which has been tied to longer recovery times, falls, dementia, higher re-hospitalization and worse medical outcomes. On the other hand, reduced noise levels in intensive care units have been found to promote better sleep and healing25.

This article is advertiser sponsored

As a general rule, designers should pay close attention to NRC and STC values and specify materials that will adequately absorb or block noise from interior environments. If specifying hard surfaces that reflect sound, absorptive materials are an absolute must and should be considered along with sound masking systems.

Conclusion

As this article has demonstrated, acoustics plays a vital role in the design of healthy and effective interior environments—spaces that facilitate learning, healing and working at their best. It should be restated, however, that the field of acoustics is complex and requires a thorough understanding of the relationship between sound and architecture to address noise effectively.

Further, each space is unique and requires a tailored approach to sound mitigation. We recommend that design practitioners’ partner with acousticians and manufacturers to address the complexities presented in their projects to deploy acoustic strategies and treatments effectively.

By doing so, architects and designers can help ensure they are creating spaces that support the sound of wellbeing, engagement and productivity.